Brian Auger & Julie Driscoll - The Mod Years (Complete Singles, B-Sides & Rare Tracks 1965-69) Brian Auger

Brian Auger was raised in London, where he took up the keyboards as a child and began to hear jazz by way of the American Armed Forces Network and an older brother's record collection. By his teens, he was playing piano in clubs, and by 1962 he had formed the

Brian Auger Trio with bass player

Rick Laird and drummer Phil Knorra. In 1964, he won first place in the categories of "New Star" and "Jazz Piano" in a reader's poll in the Melody Maker music paper, but the same year he abandoned jazz for a more R&B-oriented approach and expanded his group to include

John McLaughlin (guitar) and

Glen Hughes (baritone saxophone) as the Brian Auger Trinity. This group split up at the end of 1964, and

Auger moved over to Hammond B-3 organ, teaming with bass player

Rick Brown and drummer

Mickey Waller. After a few singles, he recorded his first LP on a session organized to spotlight blues singer

Sonny Boy Williamson that featured his group, saxophonists

Joe Harriott and

Alan Skidmore, and guitarist

Jimmy Page; it was

Don't Send Me No Flowers, released in 1968.

By mid-1965,

Auger's band had grown to include guitarist

Vic Briggs and vocalists

Long John Baldry,

Rod Stewart, and

Julie Driscoll, and was renamed

Steampacket. More a loosely organized musical revue than a group,

Steampacket lasted a year before

Stewart and

Baldry left and the band split.

Auger retained

Driscoll and brought in bass player

Dave Ambrose and drummer

Clive Thacker to form a unit that was billed as Julie Driscoll, Brian Auger and the Trinity. Their first album,

Open, was released in 1967 on Marmalade Records (owned by

Auger's manager, Giorgio Gomelsky), but they didn't attract attention on record until the release of their single, "This Wheel's on Fire," (music and lyrics by

Bob Dylan and

Rick Danko) in the spring of 1968, which preceded the appearance of the song on

the Band's

Music from Big Pink album. The disc hit the top five in the U.K., after which

Open belatedly reached the British charts. Auger and the Trinity recorded the instrumental album

Definitely What! (1968) without

Driscoll, then brought her back for the double-LP,

Streetnoise (1968), which reached the U.S. charts on Atco Records shortly after a singles compilation, Jools & Brian, gave them their American debut on Capitol in 1969.

Driscoll quit during a U.S. tour, but

the Trinity stayed together long enough to record

Befour (1970), which charted in the U.S. on RCA Records, before disbanding in July 1970.

Auger put together a new band to play less commercial jazz-rock and facetiously called it the Oblivion Express, since he didn't think it would last; instead, it became his perennial band name. The initial unit was a quartet filled out by guitarist

Jim Mullen, bass player

Barry Dean, and drummer

Robbie McIntosh. Their initial LP, Brian Auger's Oblivion Express, was released in 1971, followed later the same year by

A Better Land, but their first U.S. chart LP was

Second Wind in June 1972, the album that marked the debut of singer

Alex Ligertwood with the band. Personnel changes occurred frequently, but the Oblivion Express continued to figure in the U.S. charts consistently over the next several years with

Closer to It! (August 1973),

Straight Ahead (March 1974),

Live Oblivion, Vol. 1 (December 1974),

Reinforcements (October 1975), and

Live Oblivion, Vol. 2 (March 1976). Meanwhile,

Auger had moved to the U.S. in 1975, eventually settling in the San Francisco Bay area. In the face of declining sales, he switched to Warner Bros. Records for

Happiness Heartaches, which charted in February 1977.

Encore, released in April 1978, was a live reunion with Julie Tippetts (née

Driscoll) that marked the end of

Auger's association with major record labels, after which he dissolved the Oblivion Express and recorded less often. In 1990, he teamed up with former

Animals singer

Eric Burdon, and the two toured together during the next four years, releasing Access All Areas together in 1993. In 1995,

Auger put together a new Oblivion Express. As of 2000, the lineup consisted of his daughter,

Savannah, on vocals,

Chris Clermont on guitar, Dan Lutz on bass, and his son

Karma on drums. This group issued the album

Voices of Other Times on Miramar Records one week before

Auger's 61st birthday.

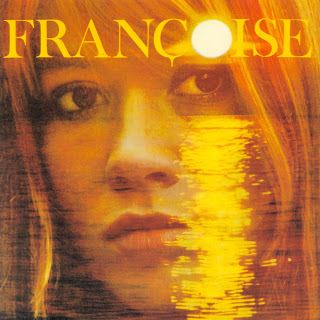

Sixties pop diva-turned-avant jazz singer

Julie Driscoll was born June 8, 1947 in London. As a teen she oversaw

the Yardbirds' fan club, and it was the group's manager and producer

Giorgio Gomelsky who encouraged her to begin a performing career of her own. In 1963 she issued her debut pop single "Take Me by the Hand," two years later joining the short-lived R&B combo

Steampacket alongside

Rod Stewart,

Long John Baldry and organist

Brian Auger. After

Steampacket dissolved,

Driscoll signed on with the Brian Auger Trinity, scoring a Top Five UK hit in 1968 with their rendition of

Bob Dylan's "This Wheel's on Fire." Dubbed "The Face" by the British music press,

Driscoll's striking looks and coolly sophisticated vocals earned her flavor of the month status, and she soon left

Auger for a solo career. Her debut solo album

1969 heralded a significant shift away from pop, however, enlisting members of

the Soft Machine and

Blossom Toes to pursue a progressive jazz direction. Also contributing to the record was pianist

Keith Tippett, whose avant garde ensembles

Centipede and Ovary Lodge Driscoll soon joined. She and

Tippett were later married, and she took her new husband's name, also recording as Julie Tippetts. With her 1974 solo masterpiece

Sunset Glow, she further explored improvisational vocal techniques in settings ranging from folk to free jazz. Two years later,

Tippett joined with

Maggie Nicols,

Phil Minton and Brian Ely to form the experimental vocal quartet Voice, and in 1978 also collaborated with Nicols on the duo album Sweet and s'Ours. A decade later, she and

Keith released Couple in Spirit, and in 1991

Tippett teamed with over a dozen instrumentalists from Britain and the former Soviet Georgia in the Mujician/Georgian Ensemble. The following year, she re-recorded "This Wheel's on Fire" as the theme to the smash BBC comedy Absolutely Fabulous. AMG.

listen hereFR

/

USA

/

UK

Chris Farlowe's second Immediate Records LP (and his second album of 1966) was probably generated more by Andrew Oldham's need for ready cash than any real need for a second long-player -- he'd had a number one hit with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards' "Out of Time" and an accompanying LP was the way to go; luckily, he had the pipes and the inspiration to pull it off. He roars out of the starting gate with a sizzling rendition of "What Becomes of the Broken-Hearted" and "We're Doing Fine," but then Oldham had him look in-house for a song, "Life Is but Nothing" by Skinner and Rose (aka Twice as Much) (which isn't nearly as strong as their "You're so Good to Me," also here), and threw on two too many additional Jagger/Richards songs, in the violin-laden "Paint It Black" and the lightweight "Yesterday's Papers" ("I'm Free," by contrast, does work), interspersed with the harder "Open the Door to Your Heart," "It Was Easier to Hurt Her," "I've Been Loving You Too Long," and "Reach Out I'll Be There," and even the Farlowe co-authored "Cuttin' In." Except for the two weaker Jagger/Richards covers (we'll forgive "Out of Time," as it sort of had to be here) and the one Skinner/Rose miscalculation, this is as strong a soul album as Farlowe's debut, and only somewhat diluted from that perfection, at the weak points. AMG.

Chris Farlowe's second Immediate Records LP (and his second album of 1966) was probably generated more by Andrew Oldham's need for ready cash than any real need for a second long-player -- he'd had a number one hit with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards' "Out of Time" and an accompanying LP was the way to go; luckily, he had the pipes and the inspiration to pull it off. He roars out of the starting gate with a sizzling rendition of "What Becomes of the Broken-Hearted" and "We're Doing Fine," but then Oldham had him look in-house for a song, "Life Is but Nothing" by Skinner and Rose (aka Twice as Much) (which isn't nearly as strong as their "You're so Good to Me," also here), and threw on two too many additional Jagger/Richards songs, in the violin-laden "Paint It Black" and the lightweight "Yesterday's Papers" ("I'm Free," by contrast, does work), interspersed with the harder "Open the Door to Your Heart," "It Was Easier to Hurt Her," "I've Been Loving You Too Long," and "Reach Out I'll Be There," and even the Farlowe co-authored "Cuttin' In." Except for the two weaker Jagger/Richards covers (we'll forgive "Out of Time," as it sort of had to be here) and the one Skinner/Rose miscalculation, this is as strong a soul album as Farlowe's debut, and only somewhat diluted from that perfection, at the weak points. AMG. / USA

/ USA / UK

/ UK

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/

/

/  /

/